The Disunited Kingdom – Radical federalism and the search for a new common-wealth

Do not underestimate the scale of the democratic crisis facing Britain. Don’t kid yourselves either that it isn’t going to get a lot, lot worse.

Do not underestimate the scale of the democratic crisis facing Britain. Don’t kid yourselves either that it isn’t going to get a lot, lot worse.

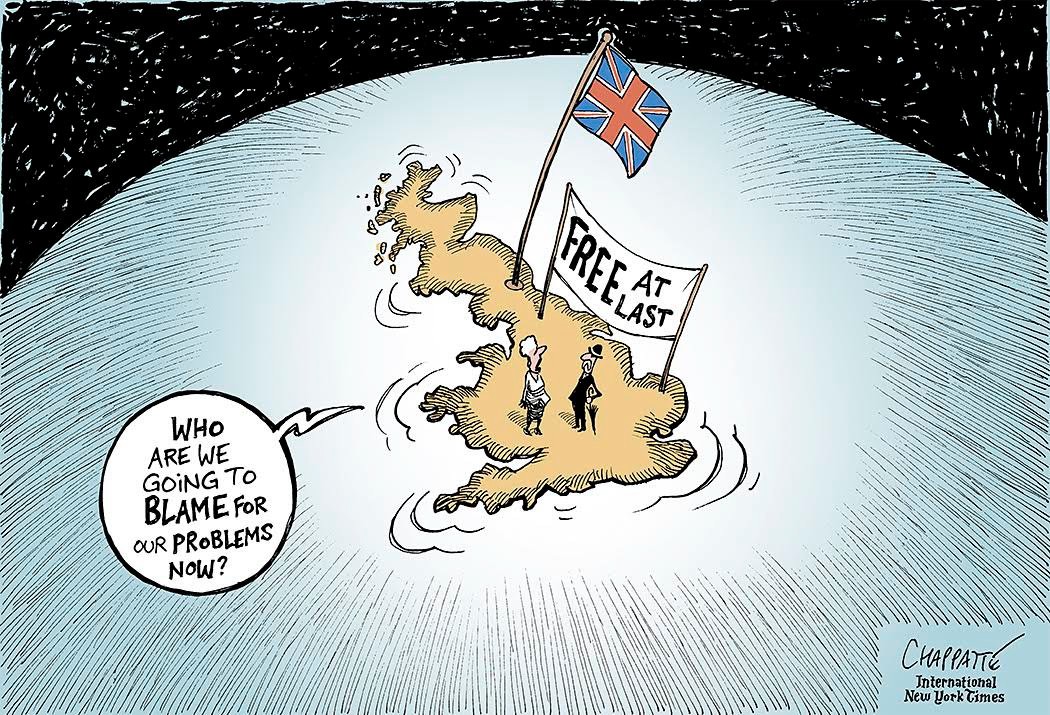

Brexit opened up wounds that will not easily heal. Mythical claims, wrapped up in sovereignty and identity politics, looked a lot different when viewed from the rotting mounds of fish that could not be exported from our ‘sovereign’ lands.

It looked no better from the lorry queues, the hard borders and paperwork mountains that have all come with Britain’s new notional independence. And after that, the disappearance of unrestricted rights to

move, study, drive and access health care in Europe seem to have taken many by surprise…“What are they thinking of, for God’s sake, don’t they know we’re British?!?”

But if Brexit opened up awkward wounds, Covid and climate could prevent them healing.

We are on an existential roller-coaster like no other. Surviving it requires a new politics – a new democratic settlement – that goes well beyond the fanciful claims of micro-nationalism and identity politics. That’s what makes the radical federalism ‘We, the People’ pamphlet1 such an interesting starting point.

Any post-Covid economics able to survive the coming climate upheavals cannot look remotely like the economics that took us into them. And a new democratic settlement cannot replicate the old one. This presents huge challenges to both Left and Right. It requires a complete re-think of what tomorrow’s meaningful democracy and sustainable economics must look like. One without the other would become another unstable illusion.

Jihadi libertarians

If such a rethink is difficult, it will be made all the more complicated if George Monbiot is correct. Monbiot’s contention is that we now have a Conservative Party at war with itself. Like the Republicans in the States, Britain’s Tories are locked in a civil war between old-style patricians (happy with the benevolent dictatorship that limited democracy offers) and jihadi libertarians who would dump democracy in favour of a corporately dominated, free-for-all.

Britain’s tidal wave of patronage contracts handed out during the pandemic suggests that the jihadis are winning. If so, then expect the Tories to play division and fragmentation cards in much the same way Trump did. Instead of a radical re-casting of democratic rights and accountability, libertarians will fan the tides of resentment and hostility.

One obvious ploy would be to use the LSE study claiming that Independence would cost Scottish taxpayers an extra £2,000-£3,000 a year. The Right won’t care how this goes down in Scotland. Their target would be English resentment. “Why pay for Scottish freeloaders? If the Scot’s want to go, let them pay their own way.” Scotland may say ‘Fair enough’, but England’s drift into corporate feudalism will insist on writing all the rules about Scottish participation in the UK economy. It is how their Uncommon-wealth works.

Those who see Scotland rejoining the EU, with a wider/fairer market to play in, should look carefully at the Irish debacle over the North Sea border and the fish fiasco. Don’t think that a Trump Wall is beyond the dreams of jihadi Conservatives. Stoking the fires of Northern resentment and hostility might be their ploy for holding on to English seats taken in the last election. It worked well enough for Brexit. Why not Scotland?

Jihadi libertarianism would happily run with ‘English jobs for the English’, ‘English health care for the English’, ‘English vaccines for the English’, etc. Anything that avoids structural transfers of wealth from the rich to the poor would suit them fine. And setting the poor against the poor is so much easier, especially when helped by your enemies.

Before the first cheers of a new ‘democracy debate’ died down a host of charlatan claims sought to narrow the choices on offer. Nationalists want to chase nationalism. Yesterday’s Establishment call for a Royal Commission on the Constitution to overhaul and oversee change; a long, slow process in which the Great and the Good would review centralised power without letting go of it. Both are remote from the radical federalism proposals advocated by ‘We, the People’ pamphleteers.

Picking the wrong fights

Labour lost the Brexit debate because it allowed the Tories to set the terms. Arguments that should have been about austerity got dressed up as ‘sovereignty’. Naive nationalism won because corporate capitalism went unchallenged. The chasms dividing Britain’s richest and poorest barely figured. As rooted in New Labour legacies as in Cameron’s platitudes, short-term, deregulated capital effectively owned both.

Casino economics in the South (systematically pricing the young and poor out of decent housing) never even bothered to get on a train up North. There, people whose lives looked out on hardship, abandoned shops, empty factories, crumbling schools and underfunded hospitals, just wanted someone to blame. Brexit copped it. Now that it has resolved nothing, someone else must be blamed.

Democracy was always going to be next in line, and with good reason. Britain is the most centralised state in Europe. Its illegitimacy needed to be thrown into question. Politicians who sheltered behind the ‘facade democracy’ claims of the Westminster wonderland now face tidal waves of public skepticism. But unless wealth redistribution comes hand-in-hand with power redistribution, all reforms would end in tears.

Re-structuring the House of Lords, the Privy Council, Constituency boundaries, the Bank of England and the Judiciary are all important… at some stage. But right now, the more pressing question around the Nations’ dinner tables – be they in Blackburn, Bannockburn, Bangor, Barnsley or Barry – is “Do we have any dinner?”

This isn’t a question that troubles the rich. Those who profited most before the pandemic have profited most from it. In October 2020 Forbes magazine reported that, in 3 months, US billionaire wealth had increased by 27%(!), largely thanks to government stimulus packages. It was much the same in Britain. Not once has Britain’s Chancellor suggested that the richest – often banking offshore and paying zero UK taxes

– should pay for the chasms dividing the rich from the rest in our Disunited Kingdom.

A democracy that sustains such divisions cannot survive. Patronage contracts handed out for public services are a path from democracy to kleptocracy. Were it not for the pandemic, and the death of parliament, we would have been comparing Johnson’s Britain with Yeltsin’s Russia. An era of the oligarchs unfolds before our eyes. Fresh fish no longer make it out of British ports but dirty money and patronage slosh in and out of the economy (tax-free) as they choose. No wonder democracy itself is being challenged.

Synthetic solidarities: the community of communities

Those seeking a more meaningful and inclusive democracy, however, need to start from somewhere else. It is here that the elements of a serious re-set can be found. In reality, all states are synthetic constructs. Our vulnerabilities and shared interdependencies are what hold us together. Cultural separatism chases these into divisive cul-de-sacs. Climate emergencies demand the opposite. Mutuality and inclusion become the glue that matters.

You could see this when Covid first struck; in the ways people shopped for each other, phoned to check the neighbours were ok, and (indirectly) when people volunteered for vaccine trials that might (eventually) keep others alive. You could see it too when Germany sent a plane load of doctors to help Portugal’s hospitals

cope. And in Oxford’s insistence that, in developing nations, their vaccine cannot be sold for a profit. It is also the social solidarity that has underpinned our NHS and Blood Transfusion Service for over 70 years.

The next set of climate crises will force us to build on these lessons rather than on the mess preceding them. Politicians have already been told that centralised policies alone cannot deliver the scale of carbon reductions needed to meet Britain’s climate targets. Environmental stability demands far greater decentralised powers, duties and resources. The localisation of our interdependencies must then be turned from a crisis measure to a source of strength.

Such solidarities will matter far more than national boundaries. Westminster, Hollyrood and the Senedd can hold the gates open to this process but they cannot be allowed to own it. Maybe Wales grasps this better than Scotland or England.

In a thoughtful piece in Planet Digital, Selwyn Williams argues that we should follow the lead of Community

Movement Cymru; thinking of ourselves more as a community of communities’2 than a set of divided

nations. Internationally, the model he draws on is of the Swedish Rural Parliament. This biennial gathering of 1,000 representatives from towns, villages and communities, makes its own representations directly to the Swedish government and parliament. It offers a more coherent framework (of both accountability and continuity) than the ad hoc Citizens Conventions Britain has dabbled in.

The bloody English

Such a ‘Parliament of the Communities’ would also help us get past ‘the English problem’. In truth, only the Far Right really hanker after an English parliament. England’s divisions run much deeper. North-South hostilities are everywhere. So too are tensions between metro-mayors and elected leaders of the councils within their domain. Then there’s the resentment of major cities excluded from the metro-club, and the angst of rural areas excluded by everyone.

And, if we’re being brutally frank, most elected authorities have lived in austerity bunkers for so long that the idea of opening the door to their own communities counts as more of a threat than an invitation. Yet it is within such limitations that the building of a new democracy must begin.

The climate emergency will force us to live within rapidly reducing carbon budgets. Localising (and cutting) our carbon footprint will become the new security norm. Covid forced us to live within a ‘contagion- reducing’ economy. Climate will do so in a ‘carbon-reducing’ one. The difference is that community involvement will become part of the answer, not the problem.

Of course, grass roots democracy will get things wrong. Communities will do things differently. Some will work, some won’t. The best lessons will be shared, the worst abandoned. European examples of such federalism display it as a strength, not a weakness. So, in the words of Leonard Cohen –

Ring the bells that still can ring Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything That’s how the light gets in.

This is the challenge facing those wanting a new democratic settlement. Put communities before capital, climate restoration before exploitation. Forget your perfect offerings. Just be the way the light gets in.

Alan Simpson Feb 2021

alansimpson.org.uk

2 Resources of Hope in a Community of Communities, https://www.planetmagazine.org.uk/planet-online/ 241/selwyn-williams